The Mesothelioma Center News

Recent News Posts

-

news

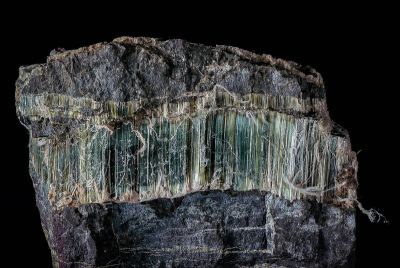

Asbestos Exposure & BansThe Environmental Protection Agency, now under the Trump administration, is reconsidering the former administration’s decision to ban the ongoing use of chrysotile asbestos. EPA…

Asbestos Exposure & BansThe Environmental Protection Agency, now under the Trump administration, is reconsidering the former administration’s decision to ban the ongoing use of chrysotile asbestos. EPA… -

news

Asbestos Exposure & Bans

Asbestos Exposure & BansExperts Warn: Talc Could Pose a Serious Health Risk

Leading scientists and doctors recently met with officials from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, participating in the FDA Expert Panel on Talc to… -

news

Legislation & Litigation

Legislation & LitigationCourt Ruling Marks Major Shift in Mesothelioma Lawsuits

The South Carolina Supreme Court has taken a major step in protecting the rights of people with mesothelioma as a result of legacy asbestos. -

news

Legislation & Litigation

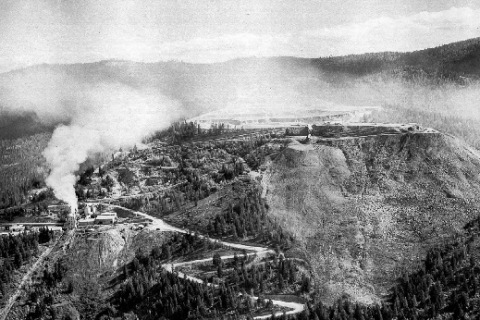

Legislation & LitigationClinic That Helped Libby Mesothelioma Survivors Shuttered

For 25 years, Libby, Montana’s Center for Asbestos Related Disease clinic, also known as CARD, has helped thousands of people with mesothelioma and other… -

news

Legislation & Litigation

Legislation & LitigationJohnson & Johnson Targets Mesothelioma Expert Again

Johnson & Johnson is trying a different strategy to discredit a reputable mesothelioma expert as asbestos claims against its talc products continue to climb. -

news

Legislation & Litigation

Legislation & LitigationJudge Rejects J&J’s $10 Billion Talc Settlement

United States Bankruptcy Judge Christopher M. López of the Southern District of Texas has denied Johnson & Johnson’s $10 billion baby powder settlement proposal. -

news

Asbestos Exposure & Bans

Asbestos Exposure & BansAsbestos Contamination Expected to Delay Wildfire Cleanup

Asbestos testing with certified asbestos consultants and other experts has been ongoing since 2 wildfires – the Eaton and Palisades fires – blazed across… -

news

Environmental

EnvironmentalFrom Toxic Pile to Carbon Sponge: Asbestos Mine Gets a Green Makeover

An abandoned asbestos mine in Baie Verte, in the Canadian province of Newfoundland, is slated for a significant environmental remediation project. BAIE Minerals, a… -

news

Legislation & Litigation

Legislation & LitigationNew Laws May Threaten Mesothelioma Payouts

Georgia, Missouri and Arkansas have now all passed bills limiting the damages people can receive and reducing the time people have to file personal… -

news

Asbestos Exposure & Bans

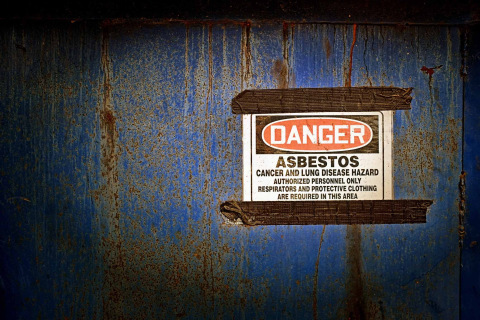

Asbestos Exposure & BansAsbestos Violations Result in Incarceration and Fines

Asbestos violations are costing some companies thousands of dollars. In one case, the court sentenced a man to jail time for his role in…