Chemotherapy for Mesothelioma Patients

Chemotherapy for mesothelioma uses drugs like pemetrexed and cisplatin to kill cancer cells. Administered through IV every 21 days, it can shrink tumors, slow cancer, relieve symptoms and improve quality of life.

How Is Chemotherapy Used to Treat Mesothelioma?

Chemotherapy for mesothelioma uses drugs like pemetrexed, carboplatin and cisplatin to kill cancer cells. Administered through IV every 21 days, it can shrink tumors, slow cancer, relieve symptoms and improve quality of life.

“In general, chemotherapy drugs disrupt the division of cells that divide quickly,” Dr. J. Marie Suga, an oncologist at Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in California, told us. “This prevents cancer cells from replicating and growing.”

Get a free mesothelioma guide with information on treatments and clinical trials.

Free Treatment GuideKey Facts About Chemotherapy for Mesothelioma

- The standard treatment for malignant pleural mesothelioma is a combo of Alimta (pemetrexed) and Platinol (cisplatin). Patients who can’t tolerate cisplatin may receive carboplatin.

- Peritoneal mesothelioma patients benefit from a cytoreduction surgery and heated chemotherapy combination.

- Chemotherapy cycles last about 3-4 weeks.

Doctors use chemotherapy as an effective first-line treatment to kill mesothelioma cancer cells. However, the drugs can also harm healthy cells. The drugs you receive depend on your mesothelioma diagnosis.

Chemotherapy is sometimes used with other targeted therapies to treat mesothelioma. Doctors also use chemotherapy to ease symptoms caused by mesothelioma tumor pressure.

How Is Chemotherapy Administered?

Chemotherapy is often delivered intravenously through an IV line. Doctors can also pump it directly into the chest or abdomen during surgery to remove mesothelioma tumors. The pumping method is called hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy. It allows for targeted drug placement, which limits damage to nearby tissues.

Patients typically receive chemo in 3- to 4-week cycles. A cycle begins with an active treatment period. This is followed by a rest period for the body to recover from the powerful chemotherapy drugs. Alimta is given one dose on day 1 of each 21-day treatment cycle with or without cisplatin. Follow-up visits usually start a few weeks after your treatment. This is especially true if you have a maintenance chemo plan.

Primary Chemotherapy Delivery Methods

- Oral or IV Chemotherapy: Known as systemic chemotherapy, it is given by doctors or nurses. They administer the drugs either orally or through an IV in a vein or a port. The drugs travel throughout the bloodstream. Patients may receive this treatment alone or with other therapies for mesothelioma.

- In-Surgery Chemotherapy: Surgeons give chemotherapy during surgery, when the cancer site is open. It is also called intracavitary chemotherapy. After warming the chemicals, an infusion pump disperses the chemo into the abdominal or chest cavity. A drain helps remove the fluid after treatment.

Intracavitary chemotherapy, including HIPEC and NIPEC, allows direct contact between the chemo drugs and the affected tissue. This reduces the impact on healthy tissue and lowers the risk of side effects. According to results from a 2023 study in the Turkish Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, “hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy following cytoreductive surgery is a preferable and tolerable method in the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma.”

Other new therapies give hope for mesothelioma patients. Preliminary data from a trial published in the International Journal of Surgery Protocols indicated following cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC with long-term IV cisplatin and intraperitoneal Alimta resulted in a 5-year survival rate of 75% for patients with malignant peritoneal mesothelioma.

Find the top cancer centers trusted by mesothelioma patients nationwide.

Get Help NowChemotherapy Drugs Used for Mesothelioma

Alimta is the standard chemo drug for mesothelioma. Doctors often give Alimta with cisplatin through an IV or port. Treatment occurs over 1 day every 3 weeks.

Some mesothelioma doctors prescribe additional chemotherapy drugs to combat disease progression after initial treatment. A 2021 study in The Lancet shows that Gemzar (gemcitabine) helps as a second-line treatment for mesothelioma.

Common Mesothelioma Chemotherapy Drugs

- Carboplatin

- Cisplatin

- Cyclophosphamide

- Doxorubicin

- Gemcitabine (Gemzar)

- Pemetrexed (Alimta)

- Raltitrexed

- Vinorelbine

Clinical trials for mesothelioma show that a combo of cisplatin and Alimta is often the best first-line chemo. Emerging research in JAMA Oncology shows that adding pegargiminase to this combo improved survival in study participants. It increased both progression-free and overall survival.

Drug combinations may also work for heated chemotherapy used in surgery. Common choices are cisplatin, doxorubicin and mitomycin C. Some chemo drugs have contraindications, so it’s important to discuss your goals and health history with your doctor before treatment.

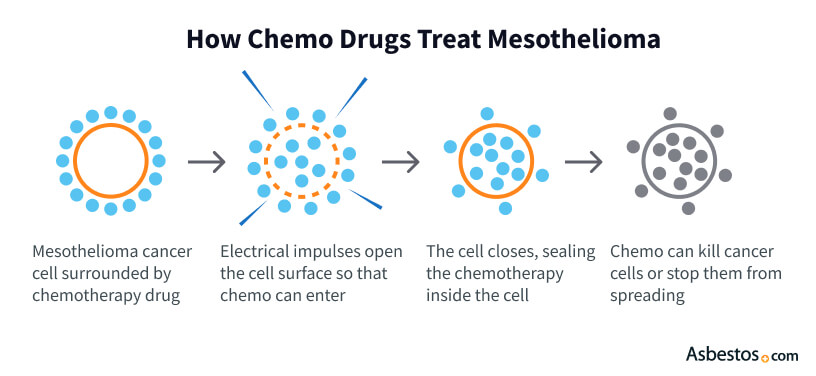

How Do Chemotherapy Drugs Effectively Treat Mesothelioma?

Chemotherapy drugs treat mesothelioma by surrounding the cancer cells. Next, the drugs enter the cancer cells and damage the control center that makes the cells divide. Once the cells cannot divide and spread to other parts of the body, the chemotherapy drugs kill them.

Combining Chemotherapy With Other Mesothelioma Treatments

Many doctors recommend a multimodal approach to treating mesothelioma. Multimodal treatment for mesothelioma combines two or more standard treatments. A recent review of multimodal approaches shows they improve overall survival rates and treatment effectiveness.

Oncologists may use chemotherapy before, during or after surgery to remove tumors. Chemotherapy and surgery are both vital for treating mesothelioma.

And so we started doing that. And every time consecutively that we went, the tumors in my body were diminishing.

To the point that, the last time that I went, the doctor says we can’t see almost anything there.

So, and I feel great. I feel that I never went through it. My feeling is right now that I have never gone through it.

I forgot all the pain and all the suffering. And I feel like I’ve never been through it, but I know I have, but it’s gone. It’s just passed.

I tell the rest of the people that are seeing me, I’m telling them that they have to what they went through, just sweep it under the rug and forget about it. Because it’s not good to going through all of that suffering again.

And I’m fine. You know, and I’m doing… it’s been a life changer for me because now I realize that I can do many things afterwards.

Now I do more things now that I’m an older person than I was when I was young.

So to all my buddies that have mesothelioma, once you get off the treatment, sweep that under the rug and keep on going forward.

“There are some very large ongoing clinical trials looking at combining both chemotherapy and immunotherapy together as a first treatment option,” Suga said. “I think cancer treatments, especially for mesothelioma, are evolving, and there’s some exciting things on the horizon.”

Immunotherapy with chemotherapy may help. It may delay disease and boost survival at established checkpoints. The combinations of durvalumab (anti-PD-L1 antibody) with cisplatin and Alimta and pembrolizumab with pemetrexed-platinum chemotherapy both resulted in statistically longer survival times than chemotherapy alone.

Another novel mesothelioma treatment approach is the use of Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields). Electric fields can disrupt the growth of tumor cells. A 2023 study tested TTFields with standard chemo for mesothelioma. The combination therapy was better than the standalone treatments because it more greatly reduced cell growth.

When I first speak with patients, they have a misunderstanding of what side effects to expect from chemo. A lot of people still think hair loss and vomiting. Explaining what most patients experience after chemo or immunotherapy infusion is talked about a lot.

Adverse Effects of Chemotherapy for Mesothelioma

Chemotherapy for mesothelioma may cause side effects such as hair loss, fatigue and chemo brain. Drug interactions can worsen side effects or weaken medications. It’s crucial to discuss any medications or alternative therapies you take with your doctor when beginning chemotherapy for mesothelioma.

Common Side Effects

- Chemo Brain: Many chemo patients have memory loss or confusion. Chemo brain can be short-lived or last for years.

- Diarrhea and Constipation: Chemo drugs often irritate the gut lining. Peritoneal mesothelioma patients may be more prone to damage.

- Fatigue: Exhaustion sometimes lasts all day. It can impact nearly all chemotherapy patients. It may even result in depression or insomnia.

- Hair Loss: Hair cells divide rapidly and so are very susceptible to damage from chemo drugs. Hair loss is one of the most common side effects.

- Low Blood Counts: Chemotherapy can lower blood cell counts. It may weaken the immune system, cause fatigue and impair blood clotting.

- Mouth Sores: Chemotherapy drugs can harm the cells in the mouth. It harms a patient’s teeth and gums, causing painful sores.

- Nausea and Vomiting: About 70% to 80% of chemo patients get nausea and vomiting during therapy. Some experience it several days later.

Rare but severe side effects are also possible. Intense headaches, unexplained bruising or shortness of breath may signal a reaction to the chemo drugs. A high fever could also mean an infection needing more treatment.

Join our upcoming webinar where two leading mesothelioma specialists explain how they tailor treatment plans to each patient’s needs.

Sign up nowHow You Can Manage Chemotherapy Side Effects

It’s vital to manage the side effects of chemotherapy for mesothelioma to preserve your quality of life. Talk to your doctor about options like changing your treatment.

Tips for Managing Side Effects

- Ask About Nutrition: Pemetrexed lowers the body’s folic acid and B12 levels. Talk to your doctor about your nutritional needs or supplements to maintain nutrient levels.

- Journal: Record new or changing side effects. Note the date, their intensity and any remedies that help.

- Openly Communicate: Don’t try to “tough it out” for fear of missing a chemo cycle. Be honest with your doctor to avoid complications.

Over-the-counter and prescription drugs, like Aloxi, Emend, and Zofran, may help. They can reduce nausea and vomiting from chemotherapy. Palliative care specialists can also provide guidance and care to reduce pain and promote comfort during your treatment.

Preparing for Mesothelioma Chemotherapy Treatment

Making a plan before starting chemotherapy can help. A plan can prevent you from feeling overwhelmed. Ask your family, friends and care providers to help. Ask the treatment center’s staff what to expect during treatment and for any tips on preparing.

Most dual-drug chemo treatments take several hours to administer. You may need a break between the two to help manage side effects.

Tips to Prepare for Chemotherapy

- Ask for Assistance. Ask family and friends to help you at home and work. Extreme fatigue often follows chemotherapy treatment, and you may need their help.

- Schedule a Dental Checkup. You may need a dental visit to check for signs of infection. Treating dental disease lowers the risk of chemo complications.

- Prepare Your Home. Remove things at home that could injure you, like sharp corners and trip hazards. Wash and cook food well to cut infection risks.

- Hair Loss: Hair cells divide quickly and are vulnerable to chemo drugs. Hair loss is one of the most common side effects.

- Complete Preliminary Testing. Blood and heart tests check if your body can handle chemo.

- Ready Yourself for Treatment. Eat a light meal, sleep well and plan for a ride to and from your appointments. Drink plenty of liquids to avoid dehydration.

- Get Port Placement. Systemic chemotherapy is usually given through a port, catheter or pump. These are surgically placed into a large vein.

Once you finish your session, you’ll need time to rest. Your body is weakened during this time, and you’ll need to avoid others with illnesses. Exercise, rest and a balanced diet can help strengthen your body during chemotherapy. Bringing a chemo bag filled with comforting and entertaining items can make treatment sessions more manageable and enjoyable. Post-chemo self-care practices include maintaining oral hygiene to avoid sores, preventing infections and learning how to take care of any medical devices or ports.

Filled with thoughtful items to bring comfort and encouragement while undergoing treatment.

Get Your Free KitCommon Questions About Mesothelioma Chemotherapy

- Is chemotherapy effective for pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma patients?

-

The best treatment for all mesothelioma types is to combine chemotherapy with another method. Chemo drugs pemetrexed (Alimta) and cisplatin after surgery can extend survival for pleural mesothelioma. For peritoneal mesothelioma, patients eligible for surgery undergo a heated chemotherapy treatment applied during the operation.

- How much does chemo cost?

-

According to chemotherapy statistics, it is expensive and can cost an average of $10,000 per month. But Medicare and other insurance plans cover most of the cost. Studies show that cancer treatment is less effective if patients can’t afford it. Many cancer patients rely on financial help during treatment. Mesothelioma patients are no exception.

Please do not hesitate to discuss finances with your doctors and their staff. They may be able to recommend options for financial assistance such as treatment grants, Social Security Disability Insurance, VA claims, asbestos trust fund claims and mesothelioma claims.

- How can chemo impact a patient’s mental health?

-

As many as 25% of cancer patients feel depressed during and after chemotherapy. Counselors, support groups, antidepressants and meditation can help. They can manage the emotional impact of chemotherapy.

Some side effects, like hair loss and weight changes can hurt patients’ self-esteem. This can lead to depression and other mental issues.

- Can I work during chemotherapy treatment?

-

Your ability to work during mesothelioma chemotherapy depends on your side effects and job demands. If you can tolerate mild side effects from a medication, you may be able to return to work.

However, your doctor may not clear you for work if your job is too risky or involves heavy labor. These hazards could cause severe harm while on chemotherapy. Always discuss your plan to return to work with your doctor before taking any action.

- How often will I need to undergo chemotherapy sessions?

-

The frequency of chemotherapy for mesothelioma can vary. It depends on the patient’s treatment plan. In general, doctors administer chemotherapy in cycles. One cycle is a treatment every three or four weeks. Rest periods in between allow the body to recover. Some patients require only a few months of therapy, while others stay on for a year or more.

The type and stage of mesothelioma affect the length and number of cycles. So do the chemotherapy drugs used. Doctors may adjust treatment plans based on the patient’s response to chemo and any side effects. Discussing your treatment plan and chemo schedule with your medical team is best.

- Are there any alternative or complementary treatments that can be used alongside chemotherapy for mesothelioma?

-

Some complementary treatments can be used with chemotherapy for mesothelioma. These treatments can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life. Some examples are acupuncture, massage therapy and yoga. Acupuncture is a traditional practice involving thin needles inserted into specific points on the body. It may ease pain, nausea and other symptoms.

Massage therapy can help reduce stress and pain and improve range of motion. Yoga improves well-being through postures, breathing and meditation. Alternative or complementary options should not replace standard medical treatment for mesothelioma. Always talk to your doctor before starting any new therapies. They can help you decide which options are safe and appropriate for you.